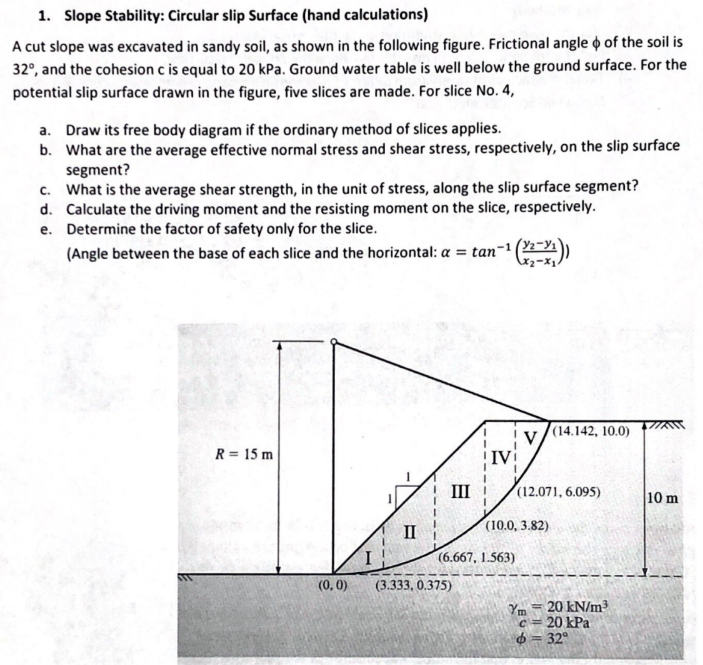

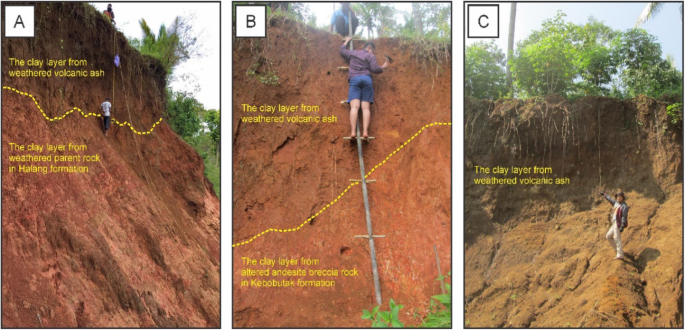

(c) Requirements- (1) Soil classification. Soil and rock deposits shall be classified in accordance with appendix A to subpart P of part 1926. (2) Maximum allowable slope. The maximum allowable slope for a soil or rock deposit shall be determined from Table B-1 of this appendix. (3) Actual slope. (i) The actual slope shall not be steeper than. Types of slopes Ac cording to extent: Infinite Slopes. The type of slope extending infinitely, or up to an extent whose boundaries are not well defined. For this type of slope the soil properties for all identical depths below the surface are same. (c) Soil erodibility information is also expanded. (d) Slope-length factor that varies with the soil susceptibility to rill erosion, is accounted. (e) A linear slope steepness relationship that reduces the amount of computed soil loss for very steep slope is incorporated. (f) A sub factor method for computing the cover management factor is. Type C Soils are cohesive soils with an unconfined compressive strength of 0.5 tsf (48 kPa) or less. Other Type C soils include granular soils such as gravel, sand and loamy sand, submerged soil, soil from which water is freely seeping, and submerged rock that is not stable.

Soils

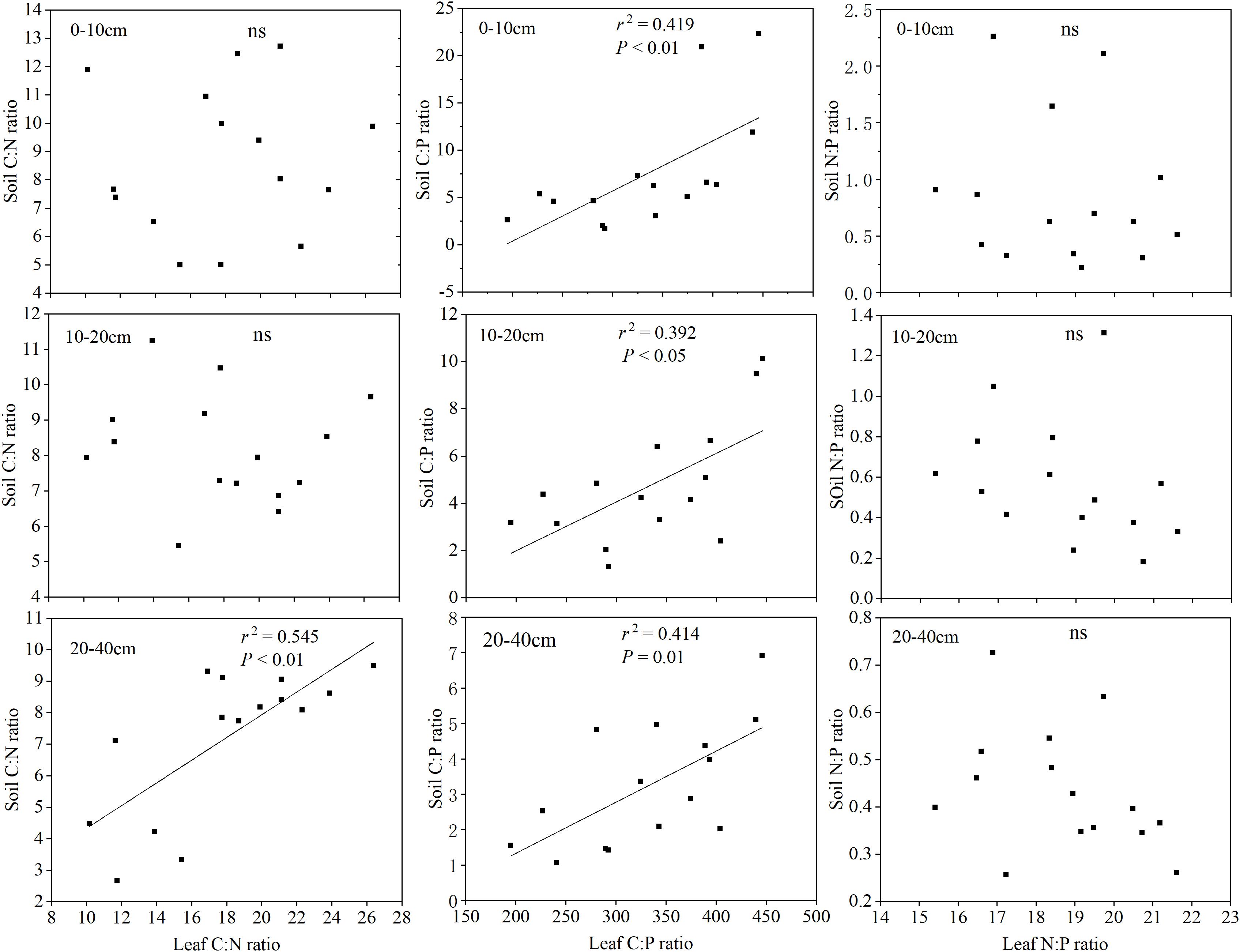

For a selected site, AgSite summarizes the site’s soils by “Map Unit Symbol” and “Map Unit Name.” The “Map Unit Symbol” serves as a code to identify a soil type. The “Map Unit Name” describes the soil type. At the minimum, the map unit name column will share the type of soil and a slope range for that soil type. In some cases, the “Map Unit Name” includes a description of erosion and susceptibility to flooding. For more information about a given soil type presented in an AgSite report’s soils table, click on the underlined code in the “Map Unit Symbol” column, and a “Soil Data Map Unit Interpretation Report” will open in a different window. Within the interpretation report, users can learn about the soil’s wind erodibility; drainage class; erosion class; physical and chemical properties; and fit with various agriculture, engineering, forestry and silviculture, grazing, recreation and other activities.

Within the soils table, an AgSite report also lists the number of acres in the selected area that has a certain soil type and the share of a selected site’s total acreage that has a certain soil type. Last, the soils table classifies soil types into one of four hydrologic groups. Soils data presented by AgSite originate from the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service’s SSURGO database, which was developed using information from the National Cooperative Soil Survey.

The following definitions and explanations provide more information that can help to interpret an AgSite report’s soils table. The explanations also share the significance of soil characteristics.

- Soil type or texture: Soil types named in the “Map Unit Name” column include a description (e.g. silt loam, clay loam, sandy clay) about the extent to which the soil has a sandy, silty or clayey composition. Sand, silt or clay composition refers to the soil’s texture. The following textural triangle illustrates the process used to name a soil’s texture based on its sand, silt and clay content. As the textural triangle indicates, soil that is one-third silt, one-third clay and one-third sand would be considered a clay loam.

Textural Triangle Describing Soil Textures by Sand, Silt and Clay Composition

Soil texture is important because it influences water retention, erosion potential, nutrient leaching, drainage capability and agricultural productivity. Sandy soils tend to dry quickly because sand particles create large pores that don’t retain water well. They also may lose nutrients through leaching and risk damage from wind erosion if they’re not covered. Clay soils, on the other hand, don’t drain well, and they may be more difficult to prepare for planting. Soils with a medium texture – not too much sand or too much clay – would create more ideal conditions for growing crops.

- Slope: Slope refers to the extent that a soil surface has an incline relative to the horizontal. In percentage terms, slope represents the elevation that occurs between two different points. As an example, if the elevation between two points that are 100 yards apart is 1 yard, then the area has a 1 percent slope gradient. In its Soil Survey Manual, the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service classifies slopes into six categories based on slope gradient ranges. Steepness increases as the slope gradient increases.

Slope Classes Named by USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

For landowners, slope has significance because it influences erosion potential. University of Wisconsin Extension suggests that soil slopes that exceed 2 percent typically erode if cultivated. When precipitation reaches the soil, its velocity and extent to which the runoff accumulates on the soil surface strengthen when slopes are steep and long. Accumulated water that moves quickly down a sloping surface accelerates erosion. For long slopes, terraces, diversions and strip cropping can address soil conservation concerns. For short and choppy slopes, implementing such practices may be more difficult. In these cases, landowners may consider coupling conservation practices with drainage systems to address runoff and erosion.

- Hydrologic groups:. The USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service developed hydrologic soil groups to describe the extent to which runoff presents a potential challenge. On an A-B-C-D scale, soils in the “A” group have the least runoff potential and the best infiltration. Conversely, soils in the “D” group have the greatest runoff potential and least infiltration. Persons that manage properties with D-rated soils should recognize the risk presented by these soils and consider conservation practices that limit runoff and erosion.

By selecting the “View map” link beside the “Soils” heading in an AgSite report, users can load a map in a separate window that illustrates the distribution of soil types in the surrounding area. The map contains the map unit symbols and boundaries for each soil type. To see more information about a particular soil type shared in the map, click on the area of interest, and the data record for that soil type will load. From the “Map Layers” window, users can choose to add or remove reference map features, such as place names, topographic elements and satellite views. By clicking the “Tools” tab at the top left hand corner of the map, a set of tools appears on the right side of the map. The “Measure Tools” tool allows users to measure a path or an area of interest.

Crop Productivity Index

The National Commodity Crop Productivity Index (NCCPI) was developed to serve as a nationally recognized, consistent tool for land valuation. One of the original reasons it was created was to help value average rental payments for parcels of land for the Conservation Reserve Program. Since its creation, it has also been utilized by the USDA’s Farm Service Agency, Risk Management Agency and Economic Research Service, and real estate assessors for assistance with purchasing decisions.

For a selected area, the AgSite Assessment Tool report displays the “Maximum Productivity Index” for different soil map units, paired with its “Productivity Index Method.” By understanding a piece of land’s soil classification and productivity potential, landowners can make more educated decisions when purchasing and/or managing land. The bottom of the soils table provides a weighted average of the productivity index for the entire selected parcel.

The National Commodity Crop Productivity Index (NCCPI), developed by the USDA National Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), is a systemized rating of United States soil for sections’ capability of growing dryland crops. The soil is rated on a scale of 0 to 1, with 1 being the highest possible rating. The NCCPI uses data from the soil survey database (National Soil Information System, or NASIS) to calculate the rating. Specifically, the NCCPI considers the land’s physical and chemical characteristics, landscape features and climate to calculate its maximum productivity under typical management (see Table 1 for detailed characteristics).

Table 1: Characteristics to Calculate Soil Rating

Type C Soil Slope Ratio

| Physical | Chemical | Landscape | Climate |

|

|

|

|

The NCCPI does not consider variable factors, such as management strategies (irrigation, etc.) or land alterations (terraces, etc.).

Another important characteristic of the NCCPI is the classification of its “Productivity Index Method.” The NCCPI is categorized into three (3) commodity classifications/submodels:

- Corn and Soybean Submodel

- Small Grains Submodel

- Cotton Submodel

The “Productivity Index Method” is selected based on which commodity would grow best in the soil, based on the characteristics listed previously.

For more information regarding the Crop Productivity Index, a PDF of the USDA NRCS’s NCCPI can be found here. Additionally, a video recording of the webinar, “Update of the National Commodity Crop Productivity Index,” hosted by Robert Dobos of the National Soil Survey Center (Oct. 12, 2011), can be found on YouTube here.

Educational Resources:

To learn more about soils, University of Minnesota Extension developed a five-part educational Soil Management Series that addresses basics about soil science and management practices that landowners can apply to their own land sites. The five modules discuss soil management, compaction, manure management, organic matter management, and soil biology and soil management.

The Soil Quality for Environmental Health effort has had support from multiple collaborators – those include divisions of the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Iowa State University and the University of Illinois – and it features several resources that may help landowners to learn about soil and maintain it. One tool available on the site is a Soil Problem-solving Guide. For various problems such as compaction, crop disease, salinity and erosion, the online guide lists a few indicators that would suggest that a given problem has occurred, shares several potential causes of the given problem and recommends actions that landowners can take to improve the problem. To see the problem-solving guide, go to http://soilquality.org/management/problem_solver.html.

Assistance Programs:

Class C Soil Slope Minimum

Local soil and water conservation programs may provide landowners with technical and financial assistance that they can use to preserve their soils. Funded by a parks, soils and water sales tax, soil and water conservation cost-share assistance may help landowners to implement conservation practices. In Missouri, local district offices may provide as much as 75 percent cost-share assistance for eligible activities. Examples of soil-related practices that the soil and water conservation program may entertain include those that retain topsoil. For more information, go to http://dnr.mo.gov/env/swcp/service/index.html.

C Slope Soil Test

As another assistance program to control soil erosion, the Missouri Department of Conservation provides tree and shrub seedlings to Missouri residents who will use the plants to assist with reforesting land areas, adding windbreaks and mitigating soil erosion. Between November 1 and April 15, Missouri residents may order tree and shrub seedlings from an online order form or by mailing a seedling catalog order form. For more information, go to http://mdc.mo.gov/your-property/seedling-orders-and-planting-guide/seedling-order-how.

For landowners who have highly erodible land and voluntarily participate in USDA programs, they must ensure that they adhere to Highly Erodible Land Conservation provisions. Compliance involves certifying that they agree to not use highly erodible land for planting or producing agricultural commodities unless they implement a conservation plan or system approved by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. If such a producer plans any activities that may influence complying with the Highly Erodible Land Conservation provision – demolishing fence rows is an example – then he or she should contact the USDA Farm Service Agency, which will work with the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. Failing to comply with the Highly Erodible Land Conservation provision may result in producers losing Farm Service Agency loans and disaster assistance payments, USDA conservation program benefits and federal crop insurance premium subsidies. For more information, go to http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/programs/farmbill/?cid=stelprdb1257899.

Type C Soil Slope Calculator

Sources and Other Resources:

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAO Soils Portal

- Missouri Department of Conservation, Seedling Order How-To

- Missouri Department of Natural Resources, Cost-Share Program

- Purdue University, Hydrologic Soil Groups

- Soil Quality for Environmental Health, Soil Problem-solving Guide

- Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education, Soil Management

- University of Minnesota Extension, The Soil Management Series

- University of Wisconsin Extension, Management of Wisconsin Soils

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2014 Farm Bill – Conservation Compliance Changes

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Soil Survey Manual – Chapter Three

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Soils

- USGS, Description of SSURGO Database